In this part, we're going to take our research images and our ideas and start putting them into real stage designs. Also remember that we are NOT yet talking about lights or instruments or positions or gels or dimmers or cables or any of that stuff! Right now, you're just a painter who happens to be painting with light, carefully planning out each stroke of your brush.

Please leave any comments or questions at the end. Enjoy!!

Step 4: Pull Out the Lighting

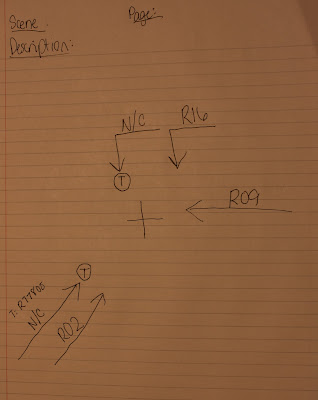

So now you're finally ready to start putting your designs down onto paper. Remember - you're still not allowed to think about positions, instruments, gel colors, gobos, or any of that! There are many different ways of approaching this next step, but I prefer to use a lighting key. A lighting key is a simple diagram that shows the general angles, colors, and textures of lights in a scene. Rather than showing a full stage's worth of lighting, however, the lighting key shows just one point on a stage, whether this is for a full stage wash or for a tiny scene played far downstage left.

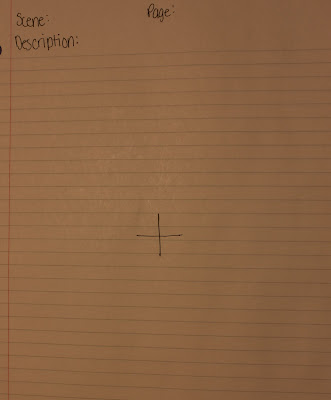

A lighting key, like much of what we do during the pre-production stages, is always changing and evolving. For every show, I dedicate an entire notebook of lined paper to lighting keys. After the template, everything is written only in pencil, to allow easy erasing and updating (for this example, I have used pen to aid in readability). Below is the basic starting point for a lighting key:

A blank lighting key. The plus sign represents the center point of the key, which can be any given point on a stage. The description should be a detailed description of how you want the lighting to affect the scene and what you want to do with the cue.

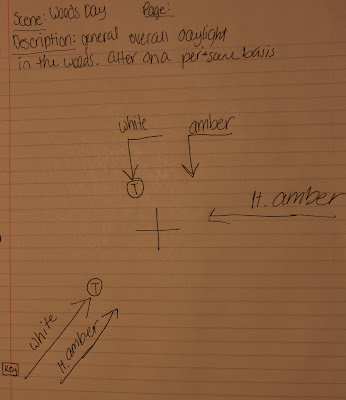

Using a pencil, you can now begin to lay out the general strokes of light that you want in this scene. For these examples, I will be using the lighting keys from my design of ELT's Into The Woods in 2009. For the following descriptions, refer to the photo below:

Each arrow on the key represents one direction, color, and angle of light. The long arrow on the bottom left of the image with the label "White" is the key light. The key light is the strongest motivated light in a scene. In an outdoor scene, the key light is often the sun or possibly the moon. Indoors, the key light could be a fireplace or a table lamp. When trying to determine the key light, just ask yourself, "what would be providing the illumination if I were actually living in this scene?". Properly identifying and using your key light is crucial to the quality and believability of your lighting design.

For this cue, the motivation for the key light came from the sun streaming through the trees (like in a forest), so I indicated that I wanted the key light to be white with a texture to it. I wrote the general color idea by the arrow, and I also put the letter T in a circle to indicate a texture. Finally, I chose to write the word Key in a box to remind myself that this was the key light in the scene.

Next, you need to identify the fill light. The fill light is any light other than the key light, which may be coming from the same or different sources of light. When the key light is a single source like the sun, the fill light will probably include reflections from walls, the floor, and anything else. Stand outside on a sunny evening before the sun sets and notice the strong key light created by the sun. Also notice that the part of your body in shadow is also lit. This comes from the reflections off any surrounding objects, and even off the air itself. When it gets darker, it may also come from street lights, car headlights, traffic signals, lamp light, campfires, or any thousands of sources. Unlike key light, you can have many, many different sources of fill light - if a fireplace is the key light, the fill light could be coming from reflections from the fire from multiple angles, moonlight through a window, light from the overhead ceiling lamp, light from the table lamp, light coming in through the door to the kitchen, and many other sources.

A good way to start your lighting keys is to literally copy the lighting scheme from your research images into your lighting key, then modify that as necessary. This is also a great exercise for any lighting designer to start becoming aware of light in the world around you. Try creating a detailed lighting key from a renaissance-era painting from one of the masters - you will learn a lot from this experience, and you may quickly discover that some of the lighting used in these paintings can't even be replicated in the real world!For this cue, the primary fill light was indirect sunlight that was reflecting from other objects in the woods. I used two main directions, one in the same direction as the key light, and one in almost the opposite direction. I also chose to make these a slightly darker color (light amber) to allow the key light to remain primary. I also used an even deeper amber from the top to further surround the actor in fill light, and the white texture from the top added even more to the feel of being in the woods.

You should constantly be making new lighting keys and modifying your old ones. This process should continue until a few weeks before tech week, when it's time to start thinking about ordering.

Step 5: Making Decisions

Now it's a few weeks before the show, and it's finally time to start making some solid design decisions. Pull out your swatch books, your gobo catalogs, and your instrument spec sheets, and let's get to work! By this time you should have been modifying and updating your lighting keys for a while, and you should have a fairly solid idea of the lighting requirements

for each cue. How to choose color is one of the most involved and personal parts of lighting design, and entire articles can be written about this alone (perhaps in the future...). However, for now, just know that as you start to decide on solid gel choices, you simply replace your general colorideas with the actual gel choices on your lighting key. The same process goes for choosing templates. For the key light, I wanted the look of light streaming through a forest, so I eventually decided on R77805: Leaf Breakup Medium (see image at right).You should continue to decide on specific gels and gobos until your entire lighting key is specified. Don't worry if you're still trying to finalize some of your choices - there's still time to finish final details. Also, keep in mind that changing gel midway through tech week is easy and quite common, as long as you have the new gel in stock. If you're really having trouble deciding between two colors, consider ordering enough of both color so you can try both and see which works best. See the updated lighting key below for an example of a completed key:

Step 6: Choose the Instruments

As a Lighting Designer, you should be very familiar with the different qualities of light that you can get from different types of instruments: Ellipsoidals (ERS), Fresnels, PAR Cans, Striplights, Follow Spots, Scoops, and whatever other instruments you have access to. It is at this point that you can start deciding what quality of light you want for each stroke of light. Without a doubt, the instrument that offers the most control is an Ellipsoidal, because of it's ability to create a hard or a soft edge, use a gobo, and use shutters in the beam. However, in many instances, the broad soft light of a fresnel or the bright punchy effects of a PAR can be more desirable. You should not be specifying specific degrees or angles of units, such as a 19 degree ERS or a Wide Flood PAR Can. Instead, you should just be choosing the ideal type of instrument that you would choose for that light source.

Conclusion

And that concludes Part II! You should now have a fairly complete list of tentative cues, a large number of research images for your show, and a sizable collection of lighting keys for each major look. You should also have a pretty solid idea of what colors and gobos you want to use in your show. These decisions are still fluid and can be changed right up until hang day.

See you in Part III!!